The following is a review of Cherry Lewis's The Enlightened Mr. Parkinson.

|

| Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. |

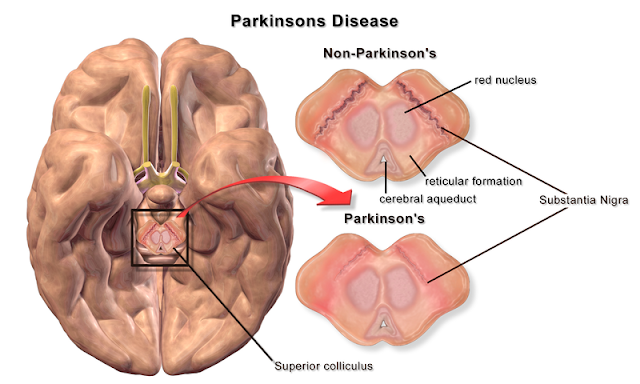

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common

neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s. (xi) It is caused by damage to the

substantia nigra, a mid-brain structure that helps to control movement. (219) Its

most salient symptoms are tremors in the limbs, difficulty walking, and

difficulty speaking.

Parkinson’s disease is named for the English apothecary

and surgeon James Parkinson, the first to identify it. Born in 1755, he lived

his entire life in Hoxton, now part of East London. (3-4) As Cherry Lewis puts

it, “James Parkinson was born into the Enlightenment on Friday 11 April 1755.

He grew up alongside the Industrial Revolution and died a Romantic on Tuesday

21 December 1824.” (1) Parkinson lived during the reign of George III. The

Seven Years’ War, the American Revolution, and the French Revolutionary and

Napoleonic Wars all transpired during his lifetime. (9) (In the United States,

the Seven Years’ War is known as the French and Indian War.)

Parkinson’s interest in the disease to which one day his

name would be affixed began with observations of passersby in the marketplace

of his hometown of Hoxton. The limbs of these men shook, and they had

difficulty walking. Parkinson approached these strangers and inquired as to

their health, learning that the condition established itself gradually in each

case. After identifying additional cases, he published his observations in the

1817 treatise An Essay on the Shaking

Palsy. (204-5) While Parkinson referred to the disease simply as the

shaking palsy, famed French physician Jean-Martin Charcot later dubbed the

disease Parkinson’s disease. (218)

While the precision with which Parkinson described the

disease and its progression is impressive, he did make a few erroneous claims.

The first regards sleep. Parkinson claimed that sufferers of the disease

continued to shake while asleep. In fact, during deep sleep they do not. Lewis

points out those with the disease go to bed shaking and immediately begin shaking

again upon waking. (209) They are therefore left with the mistaken impression

that they continue to shake in their sleep, and Parkinson relied on these

mistaken self-reports. The second erroneous claim that Lewis mentions regards

dementia. Parkinson believed that the mind remained intact in Parkinson’s

patients, but in fact, Parkinson’s does cause dementia in some cases. (211)

Parkinson made several contributions to medicine beyond

identifying Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson once had a young patient who was

bitten by a dog. After investigating the matter, he decided that the dog was

healthy and that therefore the boy did not need to fear rabies. However, the

boy did subsequently develop rabies. This was the first time that Parkinson

became aware that asymptomatic dogs can still spread rabies, a phenomenon not

recognized by his peers, but which he brought to their attention. (104-5)

Parkinson was a contemporary of Edward Jenner and became and enthusiastic

practitioner and proponent of vaccination. (129) Parkinson successfully pushed

for the creation of the first separate fever ward in London, and he even

authored a “benchmark” paper on lightning injuries. (194-5, 29) Parkinson’s son

John authored what may have been the first published case of acute appendicitis

in English. (190-1)

Parkinson was awarded a medal by the English Humane

Society. The award was bestowed upon him for having resuscitated a man who had

attempted suicide by hanging. (24) The Humane Society had been founded, and

resuscitation invented, in response to the alarming numbers of people prematurely

taken for dead. (25-6)

Parkinson also embraced the Enlightenment and

participated in the radical politics of his time. Hoxton was a center of

Nonconformism, which advocated religious freedom. (9) Though Parkinson remained

an Anglican, this social milieu evidently influenced his political views. He

was a leading figure of the London Corresponding Society, authoring many of

their pamphlets, some of which offered responses to Edmund Burke’s famous defense

of conservatism Reflections on the

Revolution in France. (57) At the time, only wealthy men could vote, and among

the reforms called for by Parkinson and the London Corresponding Society was an

expanded suffrage. Though this was presumably a call for universal male suffrage, Lewis describes Parkinson

as advocating “votes for all.” (60) In addition to advocating for political

reform, Parkinson advocated for better treatment of children, supporting child

labor laws long before such laws were widely adopted, and he was among the

first medical professionals to write about the abuse of children. (110-111,

114)

Parkinson’s engagement with radical politics took place

at a time of intense alarm for the English elite. The monarchy was in

tremendous debt, the American colonies had recently won their independence in a

struggle that disrupted English trade and hence employment, and the French king

had just been beheaded. In 1797, Revolutionary France attempted an invasion of

Britain, though it was easily repelled. (100) It was in this context that

Parkinson was interrogated by the Privy Council in 1794. Parkinson’s role in

the radical fervor of this period is described primarily in chapters 4, 5, and

6.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of Parkinson’s life is

his contributions to the fields of geology and paleontology. He attended

lectures by the famed English surgeon John Hunter, and Hunter possessed a

substantial collection of fossils. Sometime between 1785 and 1788, Hunter permitted

Parkinson to view this collection, sparking his lifelong fascination with

fossils. (34, 134-5) Between 1804 and 1811, Parkinson published a three-volume

work on fossils entitled Organic Remains

of a Former World. (147, 181) James Hutton’s recognition that the Earth was

far older than previously believed, and that the surface of the Earth was being

continually reshaped, was propounded during Parkinson’s adulthood, and

Parkinson accepted these ideas. (135-6) It was also during Parkinson’s

adulthood that Georges Cuvier recognized that species can go extinct, something

disputed at the time. Cuvier’s emphasis on the significance of anatomy to

geology appealed to Parkinson, and Parkinson became one of Cuvier’s “…earliest

advocates.” (138-140, 182) Organic Remains

was extremely popular, and “…it was largely due to James Parkinson that

collecting fossils became the nation’s passion during the 1830s.” (185) Parkinson

was a founding member of the London Geological Society. (157)

Parkinson was a medical man of the eighteenth century. As

such, he was consigned to be a practitioner of many practices that today seem

absurd. At first mention in Lewis’s biography, these practices strike the

reader as comical. One medical fad of the times included blowing tobacco smoke

into patients’ rectums, for instance. (26) Whether Parkinson subscribed to this

particular course of treatment is not made clear, but he did in fact regard

bleeding, blistering, and colonic purging to be efficacious medical treatments.

The humor of it all gradually gives way to frustration that countless

well-meaning individuals of the intellectual caliber of a James Parkinson spent

the bulk of human history with little to recommend to their patients beyond

fresh air and a bowel movement.

The narrative unfolds mostly chronologically, though each

chapter focuses on a specific dimension of Parkinson’s life. The epilogue

describes the history of the family up to the present, and Lewis describes her

meeting with a descendant of James Parkinson.

Cherry Lewis, The

Enlightened Mr. Parkinson: The Pioneering Life of a Forgotten Surgeon and the

Mysterious Disease That Bears His Name (New York: Pegasus Book, 2017).

Comments